by Glenn | Jun 23, 2013 | interview, Writing

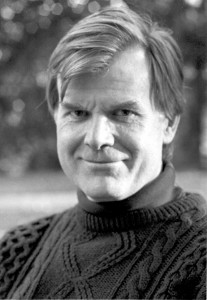

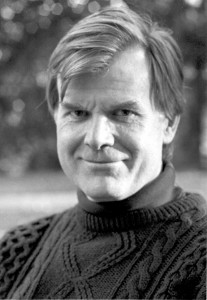

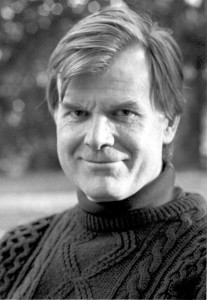

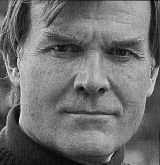

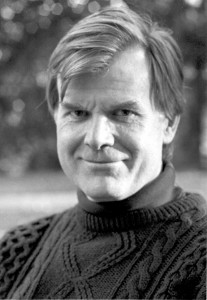

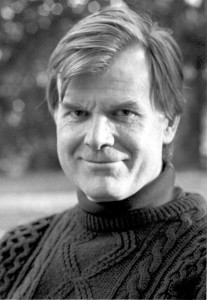

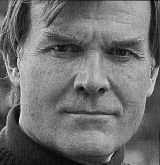

Author: Nicholas Guild

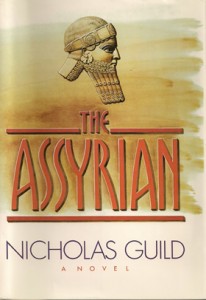

Years ago, as an aspiring writer, I read “The Assyrian” by Nicholas Guild. Since that day I have considered him one of the finest authors in the literary world—and my silent mentor of the craft. There are others who speak highly of Nicholas Guild as well…Publishers Weekly, the Associated Press, The New York Times Book Review, Book of the Month Club, The Library Journal and more, plus a long list of prominent newspapers. The list goes on, especially in international markets from Europe to Japan and Russia, but I’ll stop for now. Fast forward ahead though and today I’m honored to interview Nicholas Guild, and know him as a friend.

From thrillers, historical novels, and on to horror fiction, he has covered the realm of genres and provided novels for every reader’s enjoyment. His first novel was published in 1975 and, thankfully, we still have great works coming from him. In reviews about his novels you read what we all wish would be said about us: “…a master of timing, plot, and style…” “The most languid grace of his writings also sets the measured pace…” “…sentences are tight, well-constructed and an additional bonus, his plot and sub-plots cannot be faulted.” Formerly a Creative Writing professor at several universities, Guild now lives in Maryland.

So, this has been the shortest overview of an author whose accolades seem endless, yet that’s only part of what I want you to know about Nicholas Guild.

Last year I wrote an article about him, placed it on my website, and went on with life, never suspecting where that blog would lead. He read it, replied, and we’ve been corresponding ever since. In Guild I’ve noted extreme intelligence, yet a man who never thinks himself better than you. He is well published, far more than I could ever hope for in ten lifetimes, but he discusses writing with me as if I were a Nobel Peace Prize winner in Literature. We come from totally different backgrounds, discuss life in general, and banter about political views, yet, he treats me with the respect old friends extend one another even if they do not agree. He has complimented my work yet doesn’t spare truths about it (something I value highly in him.) I wish we had become friends years ago, but things in life seem to work out as they should, and now we are. Better late than never, I say. All said, though, Nicholas Guild is a good man. That’s as great a compliment as can be given here in Texas.

My gratitude to Nicholas Guild for the interview and sharing his experience with us. There’s something within the interview for everyone, and I hope you find food for thought.

Regards,

Glenn

Q: With the evolution of book publishing—print versus ebook or audio, agent versus indie, publishing house versus indie—how does a new author determine their first path to take, such as to go for an agent, a publishing house, or remain an indie-author?

A: Granted, the publishing business has changed a lot with the advent of the ebook, but the key to selling a book—or anything else, for that matter—is publicity. People have to know that a book exists before they can buy it. And the sad fact of the matter is that advertising an ebook is a tough business. A print book has the advantage that it will go out to prospective reviewers and that, by virtue of the fact that some publisher has bought it, some pre-selection can be assumed to have taken place. Anybody can self-publish an ebook, with the result that there are vast quantities of very junky ebooks. So how does an ebook author bring his or her work to the attention of people who are prepared to pay money to read it? Newspapers and magazines print reviews and, at present, they aren’t much interested in ebooks. My advice is to try to sell your book to a hardcopy publisher first, and this is easier to do with an agent than without. Agents at least know who to go to, so they are worth their percentage.

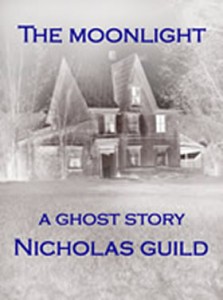

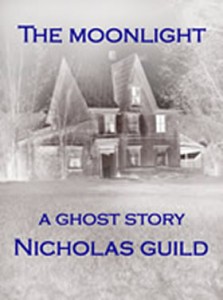

Q: Although you have an agent and have been published through major houses, your first horror/paranormal novel “The Moonlight” was published solely as an ebook as if you were an indie-author. What were your thoughts on going this route rather than taking it to a publishing house?

A: The honest answer is that my agents didn’t like the book, so I let it sit on my hard disk for nearly twenty years and then I reread it, came to the conclusion that my agent was wrong, and decided that, what the hell, I’ll do it myself as an ebook. In a sense, it was an act of desperation. I thought it was a good novel and I wanted it out there. Certainly, in the current market, I would have preferred to publish it in hardcopy first.

Q: What do you consider key habits writers should establish?

A: If you want to be a writer you should write every day, and write with care. Also, review your work regularly after enough time has passed that you’re no longer quite so in love with it and can look at it with cold eyes, as if someone else had written it. And read as much of the best work in your genre that you can find. Good models, along with the habits of regularity and self-criticism, are essential.

Q: While teaching, you had a lengthy hiatus from the publishing world. What obstacles or difficulties overall, if any, did you encounter upon your return to writing? Smooth transition back to writing or some form of personal search to find your ‘voice’ again?

A: Essentially, I found I was starting over, at least as far as my relationship to the publishing world was concerned. But during my “hiatus” I never stopped writing. I just couldn’t seem to get past the first several chapters of any project I started. I think as much as anything it was a failure of nerve, of confidence. Now I have several started novels, one of which, titled Blood, is already finished. And I’m charging ahead.

Q: Regardless of the genre, every author has research to perform for their project. Any helpful pointers? Any pitfalls to watch out for?

Q: Regardless of the genre, every author has research to perform for their project. Any helpful pointers? Any pitfalls to watch out for?

A: The only pitfall in research that I can think of is not to do it. You have to do your homework. This is particularly true in historical fiction, which is my primary area. I just finished a novel set in Greece in the 4th Century B.C. (tentatively titled The Spartan Dagger and being brought out by Tor Books—I just couldn’t resist the plug), and you have to know the details of life in that period. You can’t afford mistakes because if you make one, and the reader catches you at it, it shatters the illusion. So do a lot of reading.

Q: How connected do you become to a novel you are writing? Ever reach a point of addiction whereby you feel you must write at every opportunity or can you walk away and return to your project as you wish and still have the tempo and flow of the work?

A: Once I’ve started a book, I almost have to work on it every day. If I miss a day I tend to lose my nerve and it will take me a while to get back into it. This is just my own, no doubt neurotic, pattern. If I’m really into a book I start dreaming about it, and some of the dreams are really strange. When I was writing The Assyrian I dreamt that I ran into Sennacherib behind the counter of a dry cleaning store, where he told me, “you know, you weren’t quite right about. . .” Part of writing a novel is sustaining a fantasy, and that can do funny things to your head.

Q: Has any other profession ever come to mind that you might enjoy if you were not an author or had been a Creative Writing professor?

A: I don’t have any choice about being a writer. I have to write. It’s an obsession. But I was an English teacher for several years and I enjoyed that. Mark Twain once said about being a riverboat pilot, “I loved that profession, far more than any I have followed since.” I almost feel that way about teaching, but not quite.

Q: What do you feel are the worst or most common mistakes new or established authors make?

A: I think that both the worst and more common mistake that any writer makes is to fall in love with his own words. Scott Fitzgerald once said that every story has to go through three editing processes: one for grammar, one for style and one to cut out all the immortal stuff. When you stop being critical of your own work, you’re lost.

Q: How does the idea for a novel come about? What are your creative processes?

Q: How does the idea for a novel come about? What are your creative processes?

A: I have no idea. Sometimes an idea for a novel will just drop into my lap out of nowhere. Sometimes I’ll start with a gesture or an idea for a scene and the novel will grow up around that. Sometimes the story will have to marinate for years before I’m ready to write it. Believe me, the “creative process” is as much a mystery to me as to anyone else.

Q: New or aspiring authors often mistakenly place well established authors, such as yourself, on pedestals, and believe your work flows like honey and your lives are far different than the “everyday man.” What is an average day like for Nicholas Guild, a best-selling, international author? Any sort of routine or schedule you follow to balance life and writing? Or is your life truly champagne and caviar?

A: It sure as hell isn’t champagne and caviar. I work at writing as a job and I work at it seven days a week. A writer’s life is quiet and isolated. You have to be prepared to spend large stretches of time alone. Aside from that, I live like everybody else. It’s a mistake for a writer to imagine that he’s significantly different from other people. In the first place it isn’t true and in the second it isn’t good for your art to cut yourself off from normal life.

Q: Are there any special traits or talents which set authors apart from each other?

A: It goes without saying that a writer has to have a certain facility with language, which is probably not any difference in kind from having musical talent or a talent for fixing machines. Beyond that, in my experience most writers, at least writers of fiction, are neurotic and insecure. I have a theory that we all live mainly in fantasy until we’re about four or five, and then most people start living in the real world and the fantasy machine sort of shuts down. A writer keeps creating an imagined life for himself/herself until he/she is old and gray. Why? Probably because the writer-in-embryo doesn’t find the real world all that congenial, and the situation doesn’t improve with time. I used to tell my creative writing students, “if you find this isn’t for you, congratulations. It just means that you had a happy childhood and are reasonably well adjusted.” Fiction writing doesn’t proceed out of anything healthy.

Q: When someone approaches you and says, “I want to write a book. Where should I begin or what should I do first?” What would be your recommendation?

A: My recommendation would be, start writing. Just get stuff down on paper. It will either begin to take shape in your mind or it won’t. Writing comes first, thinking comes later. In this business there are no magic formulas.

Q: The Internet, Social Media and Networking. These have had profound impact on the publishing world. What are your thoughts on them or the future of publishing?

A: Obviously, the internet and its components are the wave of the future. In a few years hardcopy books will be a niche business. The problem is that the internet is not really set up to support something like the book business, at least not yet. We don’t have the equivalent of, say, The New York Times Book Review, where the reviews command real respect. There has to be some sort of selection process that keeps out the books that are obvious trash—although God knows enough hardcopy books are obvious trash. The internet book business needs to develop a marketing structure. I have no doubt this will happen, but it hasn’t happened yet.

Q: Who or what acts as the sounding board for your novels when you have finished a first draft and want feedback?

A: I show drafts to such friends as are willing to read them, and of course I show them to my agent, who is very good at finding what is wrong—too good for comfort sometimes.

Q: You have a large European readership, as well as in America. Do you have any projects or novels on the horizon that you can share with us?

Q: You have a large European readership, as well as in America. Do you have any projects or novels on the horizon that you can share with us?

A: I have one I’m working on at the moment which is a sort of romance for grownups. I always hate to describe the plots of my projected stories because they always sound so goofy, but it is set in the 1870’s.

Q: Where can people go to learn more about you and your writings, as well as purchase your novels?

A: Try my website, which I am sorry to say I wrote myself: http://www.nicholasguild.com. I try to have an essay on some aspect of fiction on my home page and you can read reviews and what amounts to flap copy of the novels I have available as ebooks. The ebooks themselves are available at most of the important outlets like Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Apple.

Comments are welcomed and we would love to hear your thoughts about this interview!

Want to know more about Nicholas Guild, his works, coming novels, or contact him? Try these links:

Website –http://NicholasGuild.com

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/AuthorNicholasGuild

Twitter – https://twitter.com/NicholasGuild

E-Mail – Ni************@***il.com

Amazon – http://www.amazon.com/Nicholas-Guild/e/B000APF41U/ref=ntt_dp_epwbk_0

by Glenn | Aug 26, 2012 | Writing

Glenn’s Note: I have always stated Nicholas Guild is one of the few select authors I consider as my mentor of the writing craft. After all, one should choose the best to learn from. He’s been  writing since 1975, has been published around the world with many of his works being international bestsellers, and as Publishers Weekly described him, is “…a master of timing, plot and style.” From The New York Times Book Review to the Washington Post, Nicholas Guild has received accolades aspiring writers dream of, and published authors wish for. I’m honored to present this article written by him for my website. His generosity in setting time aside to do so during his hectic schedule is truly appreciated. There is much to learn from my friend and I hope you will enjoy this as I did.

writing since 1975, has been published around the world with many of his works being international bestsellers, and as Publishers Weekly described him, is “…a master of timing, plot and style.” From The New York Times Book Review to the Washington Post, Nicholas Guild has received accolades aspiring writers dream of, and published authors wish for. I’m honored to present this article written by him for my website. His generosity in setting time aside to do so during his hectic schedule is truly appreciated. There is much to learn from my friend and I hope you will enjoy this as I did.

THE CHARACTER OF CHARACTER by Nicholas Guild

THE CHARACTER OF CHARACTER by Nicholas Guild

When I was teaching literature I had a colleague who liked to say, “There are no characters in fiction, only words,” and at the most literal level he was, of course, correct. A novel is merely another species of rhetorical performance, and when we read a story nothing happens in the world outside our nervous systems. We are only processing words.

The problem is that my colleague’s maxim is only literally true. It does not correspond to the ways people, both readers and writers, experience fiction. There is what Coleridge called “the willing suspension of disbelief.” We know, for example, that Elizabeth Bennett and Darcy are not real people and therefore they never actually fall in love, yet we always experience relief and pleasure when at last they come to a right understanding of each other. When we talk about any particular novel or story we talk about the characters as if they were real because on some level they are real for us. There is even a certain amount of neurological evidence that readers experience fiction in much the same way that we all experience real life, and with something like the same intensity.

And when we talk about characters in fiction we are not far from the way we use the word “character” in real life. For instance, when we describe some real person as a “character” we are referring to a bundle of behavioral quirks that distinguish that person. Our impression of that person is defined by peculiarities of speech, dress, behavior, appearance, etc. which he or she exhibits. Thus in our imagination Theodore Roosevelt always has pince-nez glasses, a walrus moustache and, when he smiles, enormous teeth—and he is always describing things as “bully”.

Comic characters frequently have “character” in this sense. Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield always speaks with a comic formality which is instantly recognizable and is always waiting for “something to turn up.” Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice is always expatiating on the wealth, grandeur and “condescension” of his patroness Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Mammy Yokum in Li’l Abner of blessed memory always smokes a pipe, ends every discussion with the words “Ah has spoken!” and could have beaten Jack Dempsey to a pulp. Such characters are usually what E.M. Forster described as “flat”—two dimensional and with no psychological depth, no more than the sum of their mannerisms.

Of course not all flat characters are comic. Television abounds with heroic types who are essentially flat. My personal favorite was always Steve McGarrett of Hawaii 5-O (if anyone remembers that series). He had a vocabulary of about four words—“Book ‘em. Murder One!”—and it is impossible to imagine what his childhood would have been like. But generally speaking we expect non-comic characters in fiction to have a little more depth. To use Forster’s term, we expect them to be “round”.

Of course not all flat characters are comic. Television abounds with heroic types who are essentially flat. My personal favorite was always Steve McGarrett of Hawaii 5-O (if anyone remembers that series). He had a vocabulary of about four words—“Book ‘em. Murder One!”—and it is impossible to imagine what his childhood would have been like. But generally speaking we expect non-comic characters in fiction to have a little more depth. To use Forster’s term, we expect them to be “round”.

Round characters are those we can imagine having an inner life. They are allowed, even expected, to exhibit contradictions. They are human the way we are human.

But to my mind there is one possible difference. Our sense of “character” in fiction is in many ways close to another way we use the word in real life, which is essentially moral. We speak of people as possessing “character” as an attribute, like eye color. George VI of England showed “character” during World War II by identifying himself personally with the goal of victory. He refused to let his family seek safety in Canada and he made it clear he would not come to any kind of terms with the Germans, even if England were overrun and occupied. He was prepared, apparently, to fight to his dying breath, and thus he revealed—or appeared to reveal—the core of his nature.expected, to exhibit contradictions. They are human they way we are human.

It is open to question whether any of us really have such unified personalities. Perhaps all we have are random clusters of impulses. I don’t pretend to know. But such unity is precisely what we expect to find in fictional characters.

Of course fictional characters have the advantage of being knowable in a way real people simply are not.

Of course fictional characters have the advantage of being knowable in a way real people simply are not.

Our knowledge of the external world, and that includes our knowledge of other people, comes through the senses. We see other people, we hear them, we touch, smell and sometimes  even taste them. Yet we are constantly being blindsided by our fellow mortals and discovering that the person we thought we knew doesn’t exist, is actually another sort of person altogether, and the reason this happens is not difficult to discover.

even taste them. Yet we are constantly being blindsided by our fellow mortals and discovering that the person we thought we knew doesn’t exist, is actually another sort of person altogether, and the reason this happens is not difficult to discover.

What do we actually know about anyone else’s inner life? Only what they choose to show us, or let slip—in other words, a highly edited version.

But characters in fiction are open to us. The author, who created them, tells us what they are thinking, sometimes even gives us a transcript. Their desires and anxieties are, quite literally, an open book to us. Therefore it is possible for us to know that core we think of as the essence of each person’s private humanity.

Thus, while we only intermittently judge each other, our moral judgments of characters in fiction are relentless. It is a point writers forget at their peril: readers read from within the context of their most conservative morality.

It is also worth remembering that controlling the sympathy of a reader is a complicated business. Think of the reader as resembling a bull wearing blinders and a ring in its nose. It can only see straight ahead, and straight ahead is a direction you control. The writer creates an imaginary world and all the reader can experience of it is what he or she is shown. The writer is in control, so he or she had better be careful.

A student of mine once wrote a story about the interior life of a girl in a coma. The problem was that the girl had reached this state by mixing drugs and alcohol, which my student seemed to regard as the moral equivalent of being struck by lightning. It took me a while to convince her that the reader would judge her character negatively and that this would affect the impact of the story in ways she hadn’t anticipated and didn’t want.

A student of mine once wrote a story about the interior life of a girl in a coma. The problem was that the girl had reached this state by mixing drugs and alcohol, which my student seemed to regard as the moral equivalent of being struck by lightning. It took me a while to convince her that the reader would judge her character negatively and that this would affect the impact of the story in ways she hadn’t anticipated and didn’t want.

That was the sort of oversight which hopefully is restricted to the very young (my student, as I remember, was nineteen). Every writer wants the reader to be on the side of their hero or heroine. But the same considerations apply when you are creating a villain.

Villains are tough. If you make them too evil the reader will lose interest. Thus you have to make your villains credibly human. Why do they do all those terrible things? What do they want? The essence of the thing is that everyone has a point of view, even Jack the Ripper and Adolf Hitler, and real people are more interesting than monsters. The reader needs at least to understand the bad guy, so always provide him with a backstory.

End of sermon.

by Glenn | Jun 1, 2012 | Writing

I’ve been away from my computer for several days. I needed time to think about my writing path, plus a long list of unattended activities demanded attention. Sometimes a writer needs a break in the form of physical work. It helps clear your head and allows you to refocus on your overall efforts.

I’ve been away from my computer for several days. I needed time to think about my writing path, plus a long list of unattended activities demanded attention. Sometimes a writer needs a break in the form of physical work. It helps clear your head and allows you to refocus on your overall efforts.

On March 4th I wrote the article Missing in Action, Part 1: Author Nicholas Guild, “The Assyrian”. He’s the one author I’ve always considered the finest example of a true historical fiction writer. I wrote the article and never anticipated Nicholas Guild would read it. After all, here was an esteemed author who left the literary world with awards, accolades, and multiple published books that have been translated into several languages. Guild has never heard of me and I seriously doubt if he’s even seen my works or my website.

But today, as I returned home after finishing a number of tasks, for some reason I began to think of Mr. Guild and my article about him. I thought of how my break of several days away from writing had let me realize the urge, the desire to create, still remained and was as strong as ever. It was all passing thoughts, the kind you have when you’re tired, sweaty, and need a good shower. Yes, maybe Nicholas Guild just needed a break himself, only he was taking a much longer one than me.

Now, true story: After I showered, poured a cup of hot, fresh coffee and grabbed a cup full of my grandson’s favorite Honey Graham ‘Teddy’ Crackers to munch on (you know, those little bear snacks you can’t stop eating), I sat at my computer to check my website for comments awaiting approval. With the graham cracker container sitting next to my coffee cup, and my left hand steadily reaching in to get a cracker while I’m reading the monitor and my right hand is feverishly working the mouse, I suddenly realized I was reading a comment from Nicholas Guild—‘the’ Nicholas Guild—and that was when I reached deep into my hot cup of coffee instead of the cracker cup. With coffee flying everywhere, me flailing my hand through the air and yelling things I was glad my grandson wasn’t around to hear, I jumped out of my chair. I couldn’t believe it. First, that I had done such a stupid act, and second, that Guild had actually responded to my blog.

Rushing to wash my hands and wipe coffee off my monitor screen and desk, I finally was able to return my attention to his comment:

Rushing to wash my hands and wipe coffee off my monitor screen and desk, I finally was able to return my attention to his comment:

May 26 2012 Nicholas Guild I just read your highly flattering blog. Thank you for the kind words. I thought I’d let you know that I’m back in front of my word processor and I have a new book out in ebook form, “The Moonlight,” which is a sort of ghost story. I’m now working on another historical, set in 4th Century B.C. Greece.

Yes, after reading it four times, the words had not changed and the name remained the same—and for the sake of personal safety I moved the coffee to the opposite side of my desk. I guess God works in mysterious ways and this was His way of telling me to return to my writings. But, now how do I respond to a man I’ve always wanted to talk to without sounding like a blithering idiot? I just finger dunked my coffee cup so that spoke well of my mental faculties. During the years I performed Executive Protection, I worked with a lot of big names and heavy hitters, but here was someone I truly respected for many reasons. So I typed, then deleted, typed, deleted, and finally arrived at this:

May 31 2012 Glenn Mr. Guild, very few things surprise me anymore but seeing comments from you truly did! Your return to writing is great news and I look forward to reading more of your work. I wish you the best in all of your endeavors.

After clicking the reply button, I sat waiting for a comment to appear as if he were on the other end ready to respond immediately. What can I say? I think he is an excellent author and I was extremely happy to have received his comments to my article.

Nicholas Guild has his first ebook “The Moonlight” now out – and it’s his first try at horror. In addition to that, he is working on another historical—the first in many years. I went to his website, downloaded a sample of “The Moonlight” and intend to read it tomorrow. Nicholas Guild is returning to his writings, life is good, and my burned fingers will eventually heal….

There are a lot of lessons to be learned in this, aside from keeping crackers and coffee apart from one another while you read. We’re all human, with shortcomings, personal faults, and  problems that stir our souls. Guild was at the top of his game when he chose to take a break for whatever reasons. But he returned to writing because it’s simply in his blood to create. He may have left for a while to go teach, yet he returned. I returned to my writings after ten years away. You can’t fight what you truly are any more than a leopard can change its spots. Nicholas Guild was born to be an author. There is no denying that fact after you read one of his novels.

problems that stir our souls. Guild was at the top of his game when he chose to take a break for whatever reasons. But he returned to writing because it’s simply in his blood to create. He may have left for a while to go teach, yet he returned. I returned to my writings after ten years away. You can’t fight what you truly are any more than a leopard can change its spots. Nicholas Guild was born to be an author. There is no denying that fact after you read one of his novels.

Good luck, Mr. Guild. Someday I hope you will read one of my novels with equal pleasure as I’ve read yours. And feel free to write me any time you wish.

Warmest Regards,

Glenn

http://www.nicholasguild.com

by Glenn | Mar 4, 2012 | MIA, Writing

“MIA” Missing in Action: a casualty category assigned to the status of armed services personnel reported missing during active service, generally during combat environments.

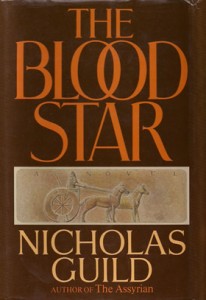

Whenever asked what authors and books have made their greatest impression on me, I always answer: Nicholas Guild “The Assyrian,” Robert McCammon “The Wolf’s Hour,” Wilbur Smith “River God,” and David Morrell “First Blood.” Each is a highly acclaimed, award-winning, well-published author in his own right. Their combined books stacked one atop the other would be almost as tall as me. And no, I haven’t read every book they published, but have managed to read quite a few.

These are authors I respect for the depth of their research and unique qualities of writing. They have served as my mentors of the craft. Each year I pull out their books, reread them as if for the first time then reverently place them away until the next year. Finding some of these authors’ books in print today is almost impossible unless you wish to pay several hundred dollars (I searched the Internet for a copy of “The Assyrian” and it was selling for $360.) Fortunately, many of their books are returning to publication in eBook formats at lesser costs.

Wilbur Smith and David Morrell remain quite prominent in the public’s eyes today. They have websites and generously communicate with their readers, especially Mr. Morrell. Robert McCammon returned from a lengthy absence, is accessible to his fans, but more will be coming on this fine author in my next blog article, “Missing in Action, Part 2: Author Robert McCammon, “The Wolf’s Hour.” But what of Nicholas Guild?

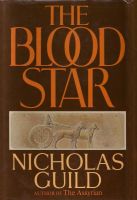

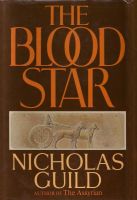

I recently completed a reading of “The Blood Star” (pub: 1989), the sequel to Guild’s “The Assyrian” (pub: 1987.) When you are wrapped within the intensity of a great author’s writings, you find yourself divided while reading their works. On one hand you anxiously devour each page, yet on the other, a sense of dread enters you because the last page is drawing near and the story will end. Nicholas Guild showed me how historical fiction should truly be written. For that I am eternally grateful.

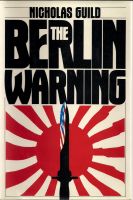

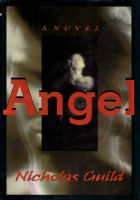

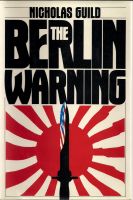

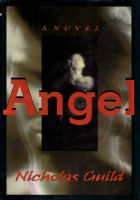

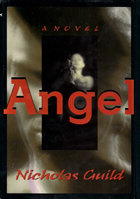

From 1975 to 1995, Nicholas wrote 11 novels. His last work, “Angel,” supposedly contains a dedication to Susan Sheridan with a rather cryptic passage from Dante’s “Devine Comedy” that translated as best I can ascertain to, “…In the middle of the path in my life, I find myself in darkness…”

I found this odd, especially with it written on his last novel. Then my former police side kicked in with its questioning, investigative nature. So many years have passed without further word from Guild. I wondered where he was today. Why had he stopped writing? Why had he seemingly fallen off the ends of the earth? No man so prominent within a professional community as he was, vanishes without reason.

What began as a simple exercise to satisfy my curiosity quickly became an intriguing puzzle and analysis of a man’s mental state. With all of its pros and cons, the Internet is an amazing tool. I found his basic bio and assorted reviews of his novels. Guild obtained his PhD at the University of California at Berkeley in 1972 and as other authors have, moved on to become a professor of English Literature at a university. Connecticut was given as his last known residence where he was enjoying life with his family. Eleven novels, his writer celebrity growing, and all came to a screeching halt in 1995 after the release of “Angel”—then he vanished like a magician upon a stage who swirls a black cloak around himself and disappears before your eyes in a cloud of smoke.

I read articles and reviews about him until my head throbbed. I realized before me was the answer as to why he had stopped writing, only the water was too muddy for me to see through. Taking a walk to think, I recalled experiences with my agent and editors of publishing houses during the same period (80’s into the 90’s) that Guild was rising in public popularity. I remembered conversations with well-published friends and the industry stories they whispered as if spies were about us.

The publishing world may appear massive and magical from an everyday reader’s perspective but in actuality, it’s a small world where few secrets exist. Editors changed employment at the big houses so swiftly then that it became the norm. Most editors were quite young during that time, not long out of college, and believed they knew what the public truly wanted and how they thought. The big houses often played favorites with their authors which created dissension over matters such as advertising and printing runs. New book ideas were often killed by editors, and authors wanting to write in different genres were frowned upon, balked at, and argued against with fervor. There was often tight-fisted reign upon authors in terms of story revisions and the next book to be written. While some of these actions proved beneficial for the industry, others became detrimental. Such was the publishing world’s environment during those years. I hope it is different now.

But the muddy water began to sufficiently clear, allowing me to see possible reasons why such a gifted writer as Nicholas Guild had turned away from his talents and became missing in action. I jotted notes upon paper and began to study each:

- Had the depth of his research, thought, action, dialogue, and characters become so demanding that by the end of the book he was mentally drained? Once you read “The Assyrian” you will fully understand the intensity I speak of here.

- Did he want to break away from his original genre path but found confrontation with his publishers?

- Did it reach a point whereby editors were attempting to overly control his writings?

- Although his writings were well acclaimed, did he discover he was not equally favored by his publisher as they had provided for with other in-house authors?

- Were there physical illnesses, some medical issue such as cancer or Alzheimer’s Disease involved which forced him to abruptly stop writing?

- Or did he simply ‘burn out’ from the constant combat in mini-battles with publishers and chose to retreat into an educational world of literature where there appeared to be fresh air for the long term?

These are all assumptions on my part. There is nothing concrete to base an answer on. But my gut feeling tells me he willingly chose the fresh air at the cost of being declared missing in action.

Wherever you are, Mr. Guild, I wish you the best in all of your endeavors. If by some miracle you should ever read this, I respectfully say, “Thank you for being one of my mentors.”

Sincerely,

Glenn

Q: Regardless of the genre, every author has research to perform for their project. Any helpful pointers? Any pitfalls to watch out for?

Q: Regardless of the genre, every author has research to perform for their project. Any helpful pointers? Any pitfalls to watch out for? Q: How does the idea for a novel come about? What are your creative processes?

Q: How does the idea for a novel come about? What are your creative processes?

Q: You have a large European readership, as well as in America. Do you have any projects or novels on the horizon that you can share with us?

Q: You have a large European readership, as well as in America. Do you have any projects or novels on the horizon that you can share with us?