MIA, Part 2: Author Robert R. McCammon “The Wolf’s Hour”

In Part 1 I discussed the highly acclaimed author Nicholas Guild being MIA, Missing in Action, from the literary world since 1995. He seemingly vanished without word to his readers and to this day has not returned to his writings. Along with Mr. Guild, I mentioned another well published author that walked away from his profession. His name is Robert R. McCammon. Fortunately for readers he returned, and has since been diligently churning out great works as before. Although he’s off the MIA list, I want to discuss his absence.

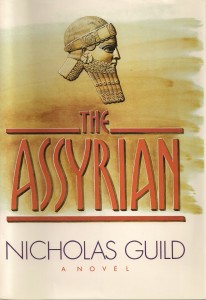

Nicholas Guild and Robert McCammon, as I previously wrote, unknowingly were my mentors. Two other authors, Wilbur Smith and David Morrell, were major influences on my writings as well. But Guild showed me through “The Assyrian” how historical fiction should truly be written, and from McCammon’s “The Wolf’s Hour,” I studied and learned so much about the craft of writing.

Born in July of 1952 (a month before me) McCammon received a BA in Journalism from the University of Alabama in 1974. While he was in college and beginning his writing career, I had been to Vietnam, was being discharged from the Corps and starting on the streets as a police officer. A highly acclaimed, award-winning, international author, he wrote from 1978 to 1991, stopped for 10 years and returned in 2002 to his writings. While searching a list of his achievements, I lost count at 23 novels, assortment of collections, anthologies, and essays. Have you ever heard of the prestigious “Bram Stoker Award?” Well, McCammon had the idea to start the Horror Writers Association where the award was born. (Aspiring horror writers owe him more gratitude than they will ever realize.)

While he was turning out his first string of published books, I was banging my head against the wall trying to complete my first book. A well-published friend and I were having a relaxing afternoon talk about writing and the industry when she handed me a book and said, “Read this then read it again if you want to learn the craft.” That was my introduction to McCammon’s “The Wolf’s Hour” (pub: 1989.) I looked at the paperback and thought she had gone crazy. A man is a werewolf who is a spy who fights Nazi’s in World War II. But my friend never steered me wrong in the past and certainly had not this time. “The Wolf’s Hour” was tightly written, had excellent action and dialogue, was an intense read, and it immediately became my craft textbook.

Even though I consider him to be my craft mentor, I’ve never met him nor have I read all of his works. One day at a bookstore I heard he was no longer writing. I checked with friends who advised me they heard through the publishing grapevine there were problems and he chose to stop. Not having an Internet to search for information as we do now, I let the matter drop. I had stopped my writings as well, (no need to rehash it, see Micheal Rivers.com interview) and so I was left with only my well-worn copy of “The Wolf’s Hour.”

The average person goes to a bookstore, finds a shelf lined with their favorite author’s novels and thinks, “Wow, they have the easy life! They just write books and don’t have to bust their butts like regular people do every day!” The perception is a make-believe world, fantasy at its best. Even today, my closest, non-writer friends have little concept of how much effort I put into writing a novel.

Highly acclaimed authors such as McCammon are placed on pedestals, separated from us common mortals. Their fingers upon a keyboard have a Midas touch and they do not suffer with daily headaches and concerns as ‘we’ do. Well, along with dressed-up rabbits laying colorful eggs at Easter, this is another misconception. (Everyone knows rabbits don’t dress-up.)

Recently, after searching for information on Guild and finding limited articles, I grew more curious about McCammon’s absence. I located his website. Everything I wanted to know was there, written by him, straight from the horse’s mouth, so to speak. I discovered other sources of information but primarily remained with his personal writings—because they were from the heart—or his writer’s soul.

McCammon’s early years held the same life tribulations as others have endured: divorced parents, lived with his grandparents, wasn’t athletically oriented, basically became a loner, and turned to writing to fill the voids of life. He started as a journalist, underwent the frustrations all aspiring writers encounter, finally became published, and later found himself in the same boat as other authors—exasperated by the antics of big publishing houses and concerned with the direction of his writings.

He found himself gradually moving into a confinement established by editors. Some of his story ideas were balked at, and when he discussed sequels to books such as “The Wolf’s Hour,” he was given poor advice which compounded later discouragements in his life. Confinement is nothing more than caging an author. I believe an author should write the stories swirling in their heads, regardless if you cross into different genres or vary from an editor’s path. For McCammon, he evidently felt the same because confinement began to wear on him. Another frustrating factor was the path he saw the horror genre taking.

Where before he had seen depth and true story to horror writings, he realized they were becoming mere exercises in the spewing of blood, guts, and gore. I liked his reference to them as ‘rubber stamping and cookie cutter.’ Even to today this is evident in numerous horror books written with page after page of pure bloodletting without a foundation of worthwhile storyline. Hollywood held a majority of this blame, while some publishing houses followed suit solely in the pursuit for profit. Well, money is the name of the game though, right? But it’s not right when publishers say “they know what the people want.”

In McCammon’s personal writings about his discontent and self-doubts, I took note of a true author. One who enjoyed his work being published yet was concerned about its literary worth. I saw a man who looked for writings to last the test of time, not simply be a fad and quickly forgotten.

I’m sure other issues were involved, personal issues, because when he gave his farewell, he mentioned returning to family pursuits, being a father. That was admirable. Writing is a lonely task. You must spend long hours separated from others in order to think, create, and release pent-up, pulsating ideas onto paper.

Some of the articles I read about McCammon mentioned depression. Battling depression is as easy as standing on the beach and trying to hold back the waves of the ocean. I know because my father suffered with it before he died.

The more I read about Mr. McCammon, the more I respected him. And in his recent website article, “My Calling,” he openly discusses his absence and return. It takes a lot of courage to tell the world as he did that he had shortcomings and doubts about himself as a writer. Very few people will ever mention their shortcomings. But, read it yourself. There’s a lot you as a writer should digest.

I found myself making comparisons to Mr. McCammon. Okay, so I don’t have over 5 million of my books in print as he does, but there were some similarities. He gets his ideas from anywhere, even a dream. One of my books came from a dream. He doesn’t work from an outline. Neither do I. He sees the story in his head and writes what he sees. Well, ditto. Sometimes I’m surprised at what comes next as I write too.

Yes, Mr. McCammon, as you said, “…writing is the mystic journey that cannot be shared by anyone else… It is a solitary trip, with an uncertain destination.”

Robert R. McCammon is a fine man. I’m glad he’s off the Missing in Action list.

He’s the kind of man I’d enjoy sitting on the porch with, smoke a cigar and share some Jack Daniels, and have a leisurely conversation about the world in general—one of those talks where you right all the wrongs and walk away happy.

Until that day, all the best to you, sir.

Glenn